By David Barry – 1978

Old Charley doesn’t come upon the hill to race anymore, but he’s the fastest legend on Mulholland Drive because nobody ever conclusively beat him. The kids racing Mulholland now fancy themselves championship drivers and they’ll tell you Charley was king of the hill more because of his car than his driving. Charley raced a hellacious 427 Corvette with rear tires as wide as the business end of a steamroller and enough horsepower to haul a freight train. They talk as if all he had to do in that car was put his foot down and steer.

Legend has Charley blasting through turns with the tires smoking and the rear end dancing and grabbing for pavement so hard it practically ripped up the asphalt. Old Charley, they say, drove with one hand on the wheel and the other around a beer can, a real gee-aw leadfoot cowboy arm-wrestling his car around the circuit and tossing empties behind him.

Charley began racing Mulholland about 1960 in a modified ’51 GMC pickup. The fun then was running Sunset Boulevard sports in their Jaguars, MGs, Corvettes and Porsches, and rubbing their noses in the shame of losing to a maniac in a truck. Charley moved to more sophisticated racing equipment — a ’55 Ford station wagon, Hillman Minx, another truck and several other unlikely racers before the Corvette.

Mulholland racing is so dangerous one might compare it to a children’s game of cowboys and Indians played with real guns and live ammo. For reasons nobody understands, none of the serious racers have been killed and few have been badly hurt, despite dozens of horrendous crashes over the years. Charley wears a scar from an end-over in the pickup truck and came close to passing away after a head-on collision in a blind turn.

Charley wouldn’t want to race most of the kids up there now because they drive minor-league stuff like Capris, trick Volkswagens, Datsuns and Toyotas. He’d want to run Chris, the current king of the hill.

Chris is a serious, intellectual type who lives near Mulholland and built his own racer after deciding that the fastest production Porsche wasn’t fast enough to make him king of Mulholland. With advice and consultation from the Porsche Works in Weissach, Germany, where he laid out $25,000 for competition parts, Chris turned a 1973 Porsche Carrera into a 165-mph racecar.

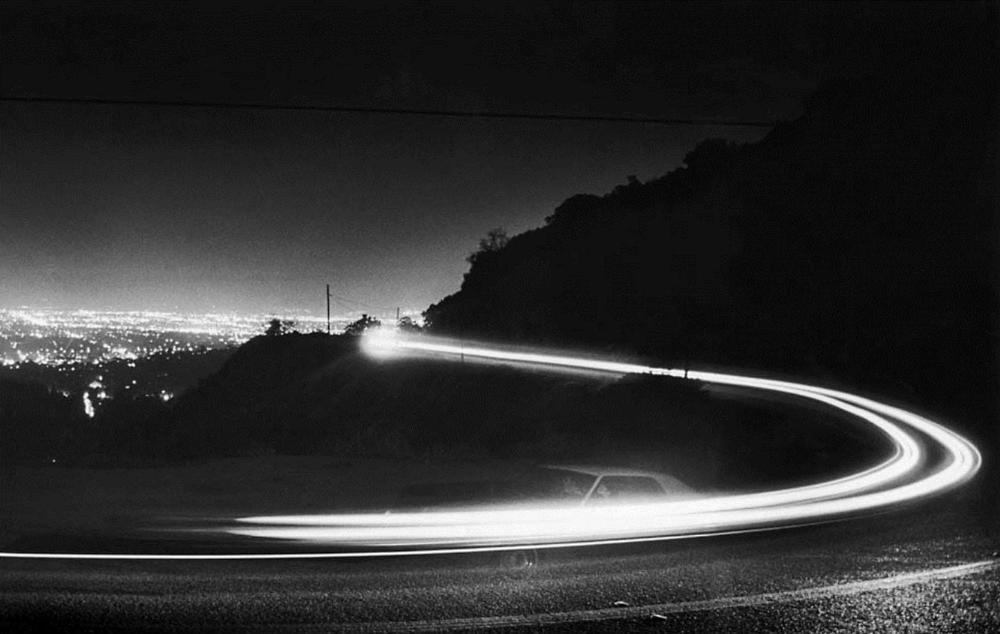

If Chris and Charley drove a match race, it would be on a stretch between Coldwater Canyon and Skyline Drive with 11 sets of turns and a pit area called Grandstands. That 1.8-mile stretch has been a Gaza Strip in a continuing skirmish between street racers and the forces of law and order since about 1960. In the daytime and early evening it’s just another segment of Mulholland Drive, a luxuriously scenic hilltop road that winds from Hollywood through West Los Angeles to the Santa Monica Mountains. On certain nights in racing season it becomes occupied territory for all-out racing from around 11 p.m. to 1 or 2 a.m. The turns are numbered and named after legends from past eras and the course is visible from Grandstands, the staging and parking area for racers, spectators and friends.

Chris is 23, older than most of the current regulars, who are ordinary-looking middle-class boys loitering between the end of high school and the beginning of a career. Most of them live with their parents and the ones with jobs work mainly to buy presents for their cars — presents like fender flares, front airdams, quartz-iodine headlight conversions, wide-rim alloy wheels, nitrogen-damped shock absorbers, racing tires and competition seats.

The racing follows its own peculiar calendar, usually heating up in the fall, cooling off in the winter, coming back in the spring and shutting down for most of the summer. Race nights have traditionally been Wednesday and Friday, but on almost any night a few drivers are likely to gather at a coffee-and-pie shop on Laurel Canyon Boulevard until it’s time to take their cars up the hill.

Mulholland racing dates back at least to 1960, but it’s several social light-years from the American Graffiti teenage rebel cruising in a Detroit muscle car with the rear end jacked up like a mating display. The game on Mulholland is driving flat-out on the short, bumpy straights and cutting lines through turns with no guardrails 600 feet above the city lights. It’s played at night on sections of road where headlights of oncoming cars show up a half a mile away and traffic is light enough for serious racing. The favored cars are Camaro Z-28s with modified suspensions, Corvettes, Porsche 911s, built-up Volkswagens with oversize tires like giant rubber donuts, or Capris, Datsuns, Mazdas and Toyotas.

Besides being dangerous, Mulholland racing is totally illegal and blatantly unfair to the unsuspecting driver who happens into a race on the way home from a party and gets several years scared off the far end of his life. Breaking traffic laws for recreation makes delinquents out of the racers, but the road is at least partly to blame. Mulholland winds and snakes along so sensuously that it brings out the closet racer in almost anyone.

A typical scenario between your average Porsche driver and a Mulholland racer would go like this: You’re rolling up Coldwater in your Porsche 911S and heading east on Mulholland at about 11 p.m. on a Friday night, basking in your $20,000 ego blanket decked out in forged magnesium wheels, Pirelli steel radials, five-speed gearbox and all that. You’ve always wanted to see what you and the car could do in a road contest and you skate up the hill from Coldwater through the Corkscrew (first of the 11 turns on the circuit) with enough revs and tire squeal to lure a car out of the pack at Grandstands. You run a line through the Grandstands’ turns, cutting across the yellow with a car on your tail, and head downhill into the Sweeper, a fast left-hander. The car closes fast behind you, quartz-iodine headlights and driving lamps cutting wild arcs through the night and stabbing your rearview mirror like drunken laser beams. The car is a $4,000 Japanese sedan and you gloat with the anticipation of a $16,000 put-down. You downshift, then punch it, holding as tight against the curve as you dare. The import stays close, but you hadn’t really been going for it.

You push harder and shoot into the next turn over your head, tires shrieking as you hang on, the Porsche’s rear end flirting with breakaway and a possible spinout. The import sticks behind you like a curse, with no apparent effort and absolutely no respect for your superior car. You fling the Porsche in the last set of curves at the outer limit of your skill, which suddenly occupies a much smaller space than you’d thought. Your sense of survival is begging your ego to back off, lose the race and live.

“Most drivers blow it up here by braking when they don’t need to,” says Mark Ralph, a 20-year-old unemployed Brentwood resident. “If you know how to drive you can go much farther into a turn without braking than most people think, even in a sedan.”

That’s how hill racers in Capris or Sciroccos shame drivers of Corvettes, Jaguars and Porsche 911s, but it’s more than knowing how to brake. It’s more than the difference between walking down a hillside and running a downhill slalom. Charley, Chris and Chris’ friend John Hall take Mulholland at speeds that grind a non-racing passenger into a whimpering casualty of total fear. The turns hurtle at you like screaming nightmares and G-forces pin you to the rail as the car drifts close to a sheer drop over the edge while the driver saws more lock on the wheel.

The tires slip, then bite, the engine rages and slams you back in the seat before the next hairpin rockets at you at 40 mph faster than you know anything can get through it. It’s like riding a roller coaster in the right-angle turn at the bottom of a ski jump going 50 mph over the limit.

None of this leisure-time activity goes unnoticed by the police, who come out in response to complaints they get from non-racing citizens. When the complaints get heavy — which is usually twice a year — the police set up a sweep to nab a bunch of racers for aiding and abetting an illegal contest of speed. The charge doesn’t last very long in court but many of the racers have spent enough time in jail before being acquitted to think twice about going back. A sweep in April 1977, that netted 32 people cut regular attendance to a handful and stopped most of the racing. A letter to the Los Angeles Times several months later complained about the hazard and asked why the police couldn’t keep Mulholland safe from the racers. Most of the racers come from households on the Times‘ home delivery list. They knew about the letter.

“They’ve really been bugging us lately,” said a 19-year-old Capri driver. “It’s gotten so it’s hardly fun up here anymore.” He read the letter.

“That’s bullshit,” he said with anger. “For every race we have, we get blamed for 20 other people making noise and trying to go fast up here because they’ve heard about us.”

Nobody felt like racing. The talk turned to accidents, police chases, tickets, court appearances, fines, license suspensions and jail sentences. The hill racers are familiar with the ins and outs of traffic law enforcement. Some of them know judges by name and a few have tickets by the dozen. Running from the police and winning is part of Mulholland racing, not because it’s fun but because stopping means getting a ticket and possibly going to jail. The heroes of the hill are drivers like Chris and John, who consistently outrun the police.

John studied the 11 curves of the racing section on foot to learn the optimum line through each degree of radius, camber change, apex and brake point. Like Chris, he lives close to Mulholland and has been driving it since he first got a license. John can run Mulholland at night without lights in heavy fog, and legend has it that he’s outrun the police more than 20 times and never been caught. He says he doesn’t keep count.

“I don’t stick around,” John says. He’s a clean-cut UCLA dropout who drives like A.J. Foyt. “If you stop when you see the cops, you get a ticket; so I keep going.” He has a disarmingly sheepish grin and a self-effacing way of talking, but there’s a case-hardened steel edge of confidence underneath.

“I wouldn’t run them anywhere but up here,” John says. “I know these roads too well for them to catch me, but I wouldn’t run them anywhere else.” A teenager pulls up in a Chevy Nova with wide-rim wheels and racing tires. The car has a four-speaker stereo system with a power booster playing a punching rock tape at high volume.

“Mark,” John says, half-turning to talk over his shoulder. “Turn it off.” Mark hesitates, gestures as if to say, ‘Isn’t it bitchin’?'”

“Turn it off,” John says with total authority. Mark walks back to his car and dutifully turns it off. “People have been complaining about noisy radios,” John explains.

Despite the letters to the Times, most of the hours on the hill are spent talking, hands in pockets, hunched against the cold. There’s no drinking, no dope and very few girls. Chris and John are constant subjects of conversation.

“Chris came by two nights ago,” says a driver parked up the street from Grandstands, and the end of another week of no racing.

“He took off from here with the rear end smoking and dancing like a fuel dragster, still fishtailing halfway down into the corkscrew.

“That car has so much power it’s hard to believe it can go in a straight line, but it handles like a Formula 1 car.”

Talk like that makes it all worthwhile for Chris — the money spent on parts, the year of designing and building a high-capacity dry-sump oil cooling system with sensors to open and close external radiators to maintain constant oil temperatures under all conditions, the fabrication of a full roll cage and chassis stiffener of space-age aluminum compound, the installation of brakes from the legendary 917 racecar, and 9-inch wheels in front and 11-inch wheels in back. The tires are made of racing rubber that wears out after three or four runs on the street.

“My dream was to build the fastest car on Mulholland,” says Chris, whose father started a lucrative chain of home furnishing stores and built a spacious hilltop home with a panoramic view.

“I looked over the Porsche racing catalog carefully, then continued with the performance representative of the factory racing division in Germany and chose the components for my car.”

Chris keeps the car on jacks under a fleece-lined cover when he’s not in it. He only drives in dry weather because the tires don’t grip damp pavement. If he’s had a drink or a smoke within 24 hours, the Porsche stays under the fleece-lined cover.

“I don’t even think about that car if I’ve been drinking,” Chris says seriously. “You can’t make a mistake in a car like that. I only drive it when everything feels absolutely right.” Chris avoids racing John. Chris says that he has the same confidence in his car as John has in his driving skill and will to win, which racers usually call balls.

“I don’t have to push as close to the limit as John does,” Chris says, “because my car is faster at seven-tenths than John’s car at nine-tenths. If John ever raced me in my car, he’d kill himself trying to beat me.”

“I’ll take on anybody in anything on Mulholland with this car,” Chris says with the pride of a father of newborn twins. “There are cars that can go faster on a race course but nothing that could go faster on Mulholland than this. I designed and calibrated the suspension — the shocks, the torsion bars, the stabilizer bars, everything — for this road. I don’t use it for anything else. It’s really just a toy.” A $40,000 toy to play with two or three times a month. Chris is said to have hit 140 mph on Mulholland and it can be reported that his speedometer passed 155 one afternoon along Sepulveda Boulevard near the intersection of Mulholland and the San Diego Freeway.

“I’ll never stop for the police in my car,” Chris says. “Not if they’re after me with the militia. There are people out there who work for the city who want to get me, but there’s no way anybody can catch me in this car. I wouldn’t stop if they set up a barricade. If they caught me, they’d impound the car and mess it up. I’d kill myself if anything happened to this car. I love it more than anything.”

The police don’t talk about individual targets on Mulholland but they’re very serious about stopping the racing. They call the racers the MRA (for the Mulholland Racing Association), initials use in the late 1960s when the racing was so heavy on Wednesday and Friday nights that several dozen cars would run in a single evening. The MRA split up after a major police bust in the late ’60s. Other groups with different sets of initials came and went, drawing police sweeps when the action got heavy.

“We were using stock equipment against racing machinery,” said Officer Jim Thompson. “They had modified suspensions, wheels, brakes and engines, which gave our cars a pretty hard time in the turns. Beyond that, they use both lanes of the road in the curves [what the racers call ‘cutting a line’], which gives them more speed. We’re not going to endanger life and property by driving both sides of the yellow.”

The Times account of the April 1977 raid described an elaborate system of staging races involving CB radios, headlight signals to spotter cars, lookouts and police-band scanners.

“They’d use their cars to block off the road at each end of the race circuit,” Thompson said, “then send a spotter car to give an all-clear signal with headlight flashes.”

The police had their own tricks, including special radio frequencies, codes and CB radios, backed up by helicopters and high-powered binoculars. Though the 1977 raid, like earlier sweeps, stopped most of the racing, chasing racers remained a dangerous game.

“I almost got taken out up there,” Thompson said of a night when he slipped through the race warning system and met a pair of racers running two abreast flat-out in a turn. In one of those instants where one’s life supposedly flashes by on high-speed videotape, the racers parted and snicked past Thompson’s car on either side and kept going. Thompson made a fast U-turn and went after them.

“I lost them,” Thompson said. “They all have switches to kill their taillights in a chase. And they know all the side roads to use as getaway routes.”

Thompson drove the Mulholland patrols without crashing, but the search-and-pursue missions were halted after several cars were written off in wrecks.

“We were afraid they’d knock themselves off up there,” said Sergeant Ronald Roarke of West L.A. “I don’t mind losing a chase or two, if that’s what they want to do, but I don’t want to lose any officers.”

The racers call the police story a fantasy, saying the discovery of a police scanner in one of the more than 20 cars involved in the bust, plus an uninstalled CB unit in another, gave rise to the story of a warning system and CB and scanners.

“It was never organized like that,” John Hall said. “The police think we go up there and plan who’s going to race and run them off against each other like drag racers. We go up there to talk and hang out and when people feel like racing, they do.” Hall added that taillight cut-off switches are considered unnecessary because the police can’t write speeding tickets against license numbers without positive identification of the driver — an almost impossible task in a night chase.

If the police can’t catch the fast drivers on the hill, they’ve taken most of the fun out of it for drivers unwilling to run for it. The ones who keep up the vigil on the hill, waiting for the racing to pick up to pre-April 1977 levels, complain of police harassment. They say officers order them off Mulholland, unlawfully stop, question and persecute them for no reason. The reason, of course, is that the police are determined to keep the racing turned off.

“We’d pull them into their pit area and talk to them, to let them know we’re there,” Officer Thompson said. “Let them know our position and we weren’t going to allow them to race. But at the same time we were there to show that we weren’t completely the bad guys. It was never a hostile situation.”

The real gripe of the drivers who still stand vigil on Mulholland from the end of prime-time programming through the Johnny Carson Show is that the racing has tapered off to a trickle. Not like the days of the MRA in the late 1960s when drivers in souped-up Mini Coopers were the terror of Mulholland.

“I’ve heard stories about Minis running three abreast, flat-out through the Sweeper in those days,” one of the racers said wistfully. “It would have been something to see Old Charley running Minis in that battleship of his. I wonder if he can still drive?”

Another racer volunteers that Charley, who has been racing since the early ’60s, maybe even the ’50s, is old — 30 or 40.

“He’s getting kinda old to drive fast up here.”

The legend of Mulholland Charley has been passed down through the various racing cliques that made Mulholland their private turf until they grew up, moved on, got drafted or married. A veteran of the pre-MRA era in the early ’60s, now a successful racecar engineer and professional driver, remembers Charley as a menace.

“Crazy Charley. He raced a pickup that terrified everybody. Nobody wanted to get near him ’cause you were likely to get run over a cliff. At the very least, you’d get hit by the flying beer cans in his slipstream.”

Mark Ralph has never actually seen Charley drive, but he’s heard the stories.

“He hasn’t been up here for a long time,” Mark says.

Old or not, Chris wants to race him; otherwise, his $40,000 Mulholland racer will languish without ever meeting the big challenge.

“If I don’t race him and beat him,” Chris says, “it’ll be like winning the heavyweight title after Ali retires. If you don’t fight him, you could never really feel like the champion.”

Charley stopped running the hill when the MRA split up around 1965. There’s never been much love lost between different groups of racers on the hill, and when Charley’s racing friends moved on, he retired. He works at a Hollywood garage.

“I don’t like to go up there much anymore,” Charley says of that hill. He’s an animated talker, with a hint of craziness in his eyes and smile. In a movie he’d be played by Al Pacino. He is 32.

“There’s too much traffic up there, too many racers who don’t know what they’re doing.” Charley still has the Corvette and his eyes gleam at the suggestion of a match race with Chris.

“Might be fun,” Charley says. “I haven’t run the Corvette in a while.” His mother is standing a few feet away, waiting for Charley to finish work and give her a ride home.

“Oh Charley,” she says, “you promised you weren’t going back up there.” Charley smiles at her and wipes his hand clean with a rag. His mother sat by his hospital bed for 11 days and nights waiting for him to come out of a coma after his head-on collision on the hill. The coma lasted 30 days.

“I’ve heard of that car,” Charley says of Chris’ Porsche. “I just don’t go up there anymore. I raced my Corvette at an old-timer’s race at Willow Springs awhile back. Turned 150 on the straight. That was a hell of a kick.

“If I were up there in my car and he came by,” Charley says, “I guess we’d have a race. If it happens, it happens.”

Credit

This article is an automotive writing classic. First run in the July 31, 1978 edition of the long-defunct New West magazine under the title “Thunder Road,” it captures a place and moment in time — a 1.8-mile slice of Mulholland Drive atop the hills between Los Angeles, California, and the San Fernando Valley during the 1960s and ’70s. The article “Thunder Road” was the basis for the 1981 film King of The Mountain starring Harry Hamlin.